Tides of Tension

A Historical Look At Staff-Commissioner Relations In the California Coastal Commission

By Todd Holmes

California Coastal Commission Project

Graphics and Design: Geoff McGhee

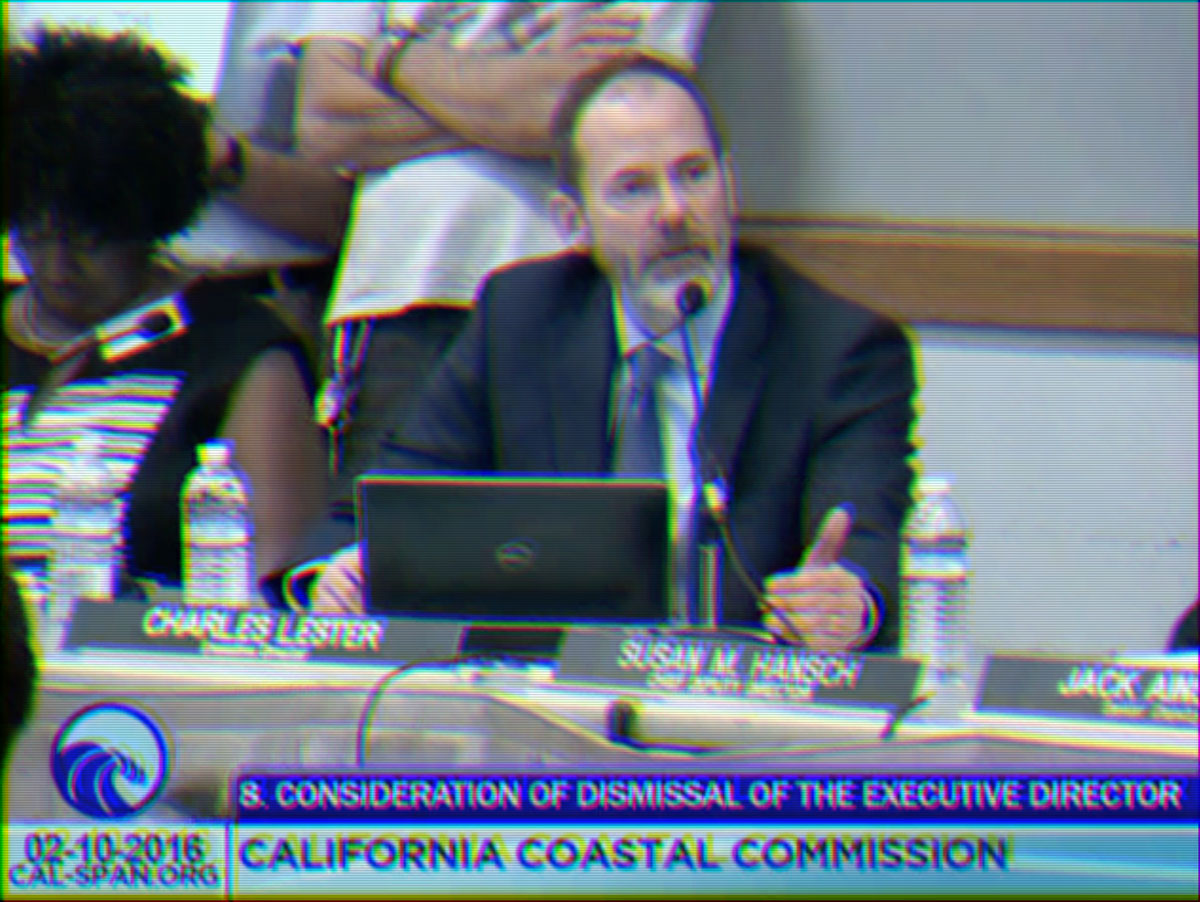

Charles Lester sighed in disbelief as the commission’s decision was read on the night of February 10. Throughout the day, scores of supporters had made their feelings and presence known on behalf of the Coastal Commission’s executive director, whose fate at the agency stood in the midst of deliberation. As hundreds inundated the meeting room with signs that read “More Lester,” many more protested outside, all expressing the dire sentiments scrolled on the surfboard held by two attendees: “Don’t $ell Out Our Coast.” Their activism did little to sway the commission, which rendered a vote of 7 to 5 in favor of dismissing Lester.

Anger pierced the room following the announcement. Some hurled insults at the commissioners; others sat in their seats and cried. And in the wake of the commission’s Morro Bay meeting, this anger continued to simmer. Many charged that Lester’s dismissal was a “power grab” by political appointees in the effort to wrest further control away from an independent staff. Others more bluntly alleged that the action was nothing short of development interests flexing their political muscle, highlighting the influence such interests now enjoy within one of California’s most powerful agencies. Across the board, reactions to Lester’s dismissal once again fueled questions of “capture”—the infamous process in regulatory governance where an agency becomes controlled by the very industry it is charged with regulating.

Yet tension, rather than capture, best explains the events that erupted at Morro Bay—a tension that long preceded Charles Lester’s tenure, and one inherent within the structure of the commission itself. The California Coastal Commission is typically discussed as a single entity, but in fact it is composed of two autonomous, and at times disagreeing, bodies. There is the staff, a dedicated cadre of civil servants whose areas of expertise range from marine biology and urban planning to ecology and law. Their staff reports must be grounded in science and law in order to survive the commission’s quasi-judicial review and potential litigation. For this reason, their recommendations must be free from outside influence. Then there is the twelve-member commission, a panel of political appointees chosen in equal proportion by the governor, assembly, and senate. This equally balanced appointment structure is unique in state government, and prevents any one entity from controlling a majority of votes on the commission—an inconvenience that has bedeviled governors of both parties for 40 years.

Map: The coastal zone along California's shore and a three-mile offshore boundary delineate the Commission's jusrisdiction. Click to zoom into locations along the coast. Mapbox and Bill Lane Center for the American West

Together staff and commissioners work in tandem to regulate development along the state’s 1,100-mile coastline. The staff draws on its expertise to advise on the legality, environmental risks, and public benefits of a proposed project. After weighing the staff recommendation and hearing public testimony, the commissioners exercise their independent judgment and officially rule on projects.

Over the decades, this structure has allowed staff and commissioners to cooperatively compile an impressive list of achievements, relatively free from direct political influence. At the same time, it has also created powerful tides of tension between Sacramento and the commission, as well as between the agency’s two bodies regarding the implementation and direction of coastal regulation. In this context, Charles Lester was not an anomaly. In fact, three of the four executive directors to serve the Coastal Commission faced threats of dismissal during their tenure. While sometimes political in thrust, the tension that ignited such standoffs between staff and commissioners was most always structural at heart: the expert versus the political appointee; the policy analyst versus the publicly accountable decision maker.

A historical look at the Coastal Commission reveals these fluctuating tides of tension, a perspective that provides a broader understanding of the structural conflicts the commission, as well as other regulatory agencies, confront.

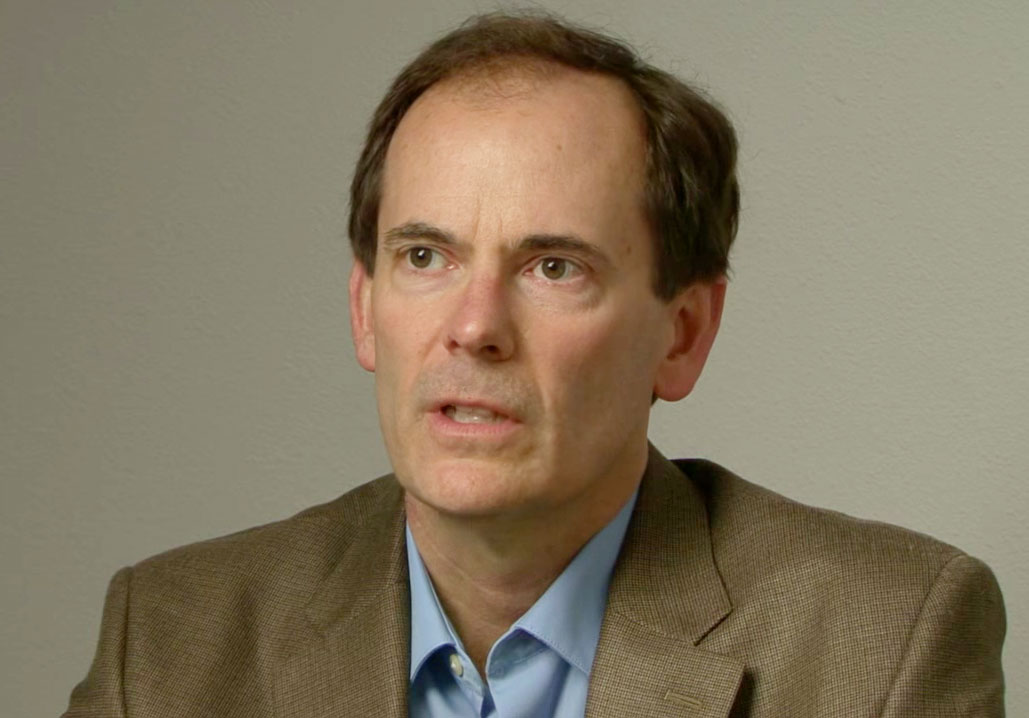

Then-Executive Director Charles Lester at the Feb. 10th hearing of the California Coastal Commission Cal-Span

Many charged that Lester’s dismissal was a “power grab” by political appointees in the effort to wrest further control away from an independent staff.

Reactions to Lester’s dismissal once again fueled questions of “capture”—the infamous process in regulatory governance where an agency becomes controlled by the very industry it is charged with regulating. Yet tension, rather than capture, best explains the events that erupted at Morro Bay—a tension that long preceded Charles Lester’s tenure, and one inherent within the structure of the commission itself.

1972-1978

The Formative Years: A Golden Age

Chairman Mel Lane & Executive Director Joe Bodovitz

The conflict that erupted publicly between commission members and staff at the meeting in Morro Bay on February 10 was a far cry from the fairly smooth internal relations that characterized the Coastal Commission in its formative years.

Created in 1972 by public initiative, the commission not only stood as the first state agency in California created by the vote of the people, but also a groundbreaking step nationally in land use and coastal regulation.

Its precedent was set in the San Francisco Bay with the establishment of the Bay Conservation and Development Commission in 1965. Both agencies were created to balance shoreline development and environmental protection. Both were also given just four years to develop long-term guidelines and successfully hone a regulatory permit process before gaining permanence. And during their formative years, both agencies rested in the hands of Mel Lane and Joe Bodovitz.

On the surface, Lane and Bodovitz could be viewed as the odd couple. Lane, a Republican businessman from Palo Alto, was co-owner of Lane Publishing, whose publications included the famed Sunset Magazine. (Disclosure: Mel Lane is the brother of L.W. "Bill" Lane Jr., whose gift helped endow the Bill Lane Center for the American West in 2005). Bodovitz, a Democrat, was a former journalist and director of the San Francisco Bay Urban Planning and Research Association (SPUR). Such perceived differences, however, became overshadowed by the values and sense of purpose they shared. Both championed the need for environmental regulation on California’s shorelines and the role of responsible public servants to guide that process. At the same time, they also emphasized the importance of balance. “It worked both ways,” Bodovitz recalled. “People had to confront the legitimate interests of both conservation and development.”

Video: Interview with Joe Bodovitz on the Bay Conservation Development Commission (transcript) Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley

A 1972 rally supporting the Coastal Act including the congressional candidate Julian Camacho * (center left), and the photographer Ansel Adams (center). California Coastal Commission

Created in 1972 by public initiative, the commission not only stood as the first state agency in California created by the vote of the people, but also a groundbreaking step nationally in land use and coastal regulation.

Mel Lane, a Republican businessman from Palo Alto, was co-owner of Lane Publishing, whose publications included the famed Sunset Magazine. On the surface, it may have seemed he made an odd pair with Bodovitz, a Democrat, who was a former journalist and director of the San Francisco Bay Urban Planning and Research Association (SPUR).

Read the 1986 Oral History with Mel Lane and Joe Bodovitz regarding their work on the San Francisco Bay Commission. Oral History Conducted by the OHC, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley)

Sunset Publishing

Together, Mel Lane and Joe Bodovitz formed a partnership that would leave a lasting legacy on the shores of the Golden State—a partnership forged just as much by the powerful interests they confronted as the unprecedented task they shouldered. That the fate of these commissions rested in their hands was not lost on either man. Nor was the well-funded wave of opposition that sought to challenge them at every step.

In response, the commission—both commissioners and staff—became a party of one. They worked together to craft a permanent plan of guidelines and develop precedents that would set the path for a regulatory permit process along the Bay and coast. They also jointly promoted philosophies that would become the backbone of coastal regulation. Among these philosophies was Misconceptions of Private Property, which asserted that owning property does not necessarily mean you have the right to alter its existing use. Another was Salami Logic, a metaphor alluding to the idea that looking at just a slice provides a very different view than if you look at the whole loaf. Essentially, what may seem harmless in one location could be absolutely devastating when multiplied along the coast.

While the partnership of Lane and Bodovitz allowed the commission and staff to operate in cooperation during its formative years, their individual contributions proved just as instrumental to the agency’s early success. Bodovitz set a new bar for assembling and managing a capable staff, providing the commissioners with sound and well-researched recommendations, and establishing a permanent plan of procedures and guidelines. He also oversaw the permit process. As chairman, Lane ran the public hearings, guided the commission’s decision making process, and presented the new agency’s policies to the public.

In many respects, Mel Lane wore two hats: he was not only chairman of the commission, but also its face and voice. He publicly rebuked critiques from the political likes of Republican Governor Ronald Reagan and his Democratic predecessor Edmund “Pat” Brown. And it was Lane, the Republican businessman, who lectured stakeholders such as U.S. Steel, Castle & Cooke, and members of the California Chamber of Commerce on the importance of balancing development and conservation. “Short term gain that causes irreversible damage to the environment,” he argued, “is just poor business.” In like fashion, he would stress the need for balance to environmental groups. Getting hit from both sides—business and environmental groups—became commonplace for Lane and Bodovitz, an aspect of the job the two men seemingly took in stride. “Environmentalists should be extremists,” Lane would say. “They represented an extreme, and the people who are going to make a buck represent the other one. The role of the decision makers is to sweat it out in the middle.”

Martin’s beach in Half Moon Bay during the mid 1970s. Lars Rosengreen via Flickr

The opposition to Proposition 20 in 1972 represented a verifiable “who’s who” of the corporate West. Such interests included Bank of America, PG&E, Standard Oil of California (Chevron), Irvine Company, Bechtel Corporation, General Electric, Union Oil, Del Monte, Lehman Brothers, and Lazard Freres, among others. They outspent supporters by a ratio of nearly 100 to 1. See Secretary of State Files, Proposition 20, 1972.

---Eureka-Times-Standard-crop-1200px.jpg)

“Conservation – Yes, But Confiscation – No!”

This clever slogan was crafted by the famed political relations firm Whitaker & Baxter, which was hired by California corporations to handle the campaign against Proposition 20. The firm's handiwork over the decades has become legendary. In 1946, it coined the term "socialized medicine" to defeat President Harry Truman's Universal Healthcare program. The firm also worked on behalf of California growers against Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers grape boycott.

From 1972 advertisement in the Eureka Times-Standard

Watch television advertisements opposing Proposition 20, the 1972 ballot measure that gave rise to the California Coastal Commission. Whitaker and Baxter collection at the state archives

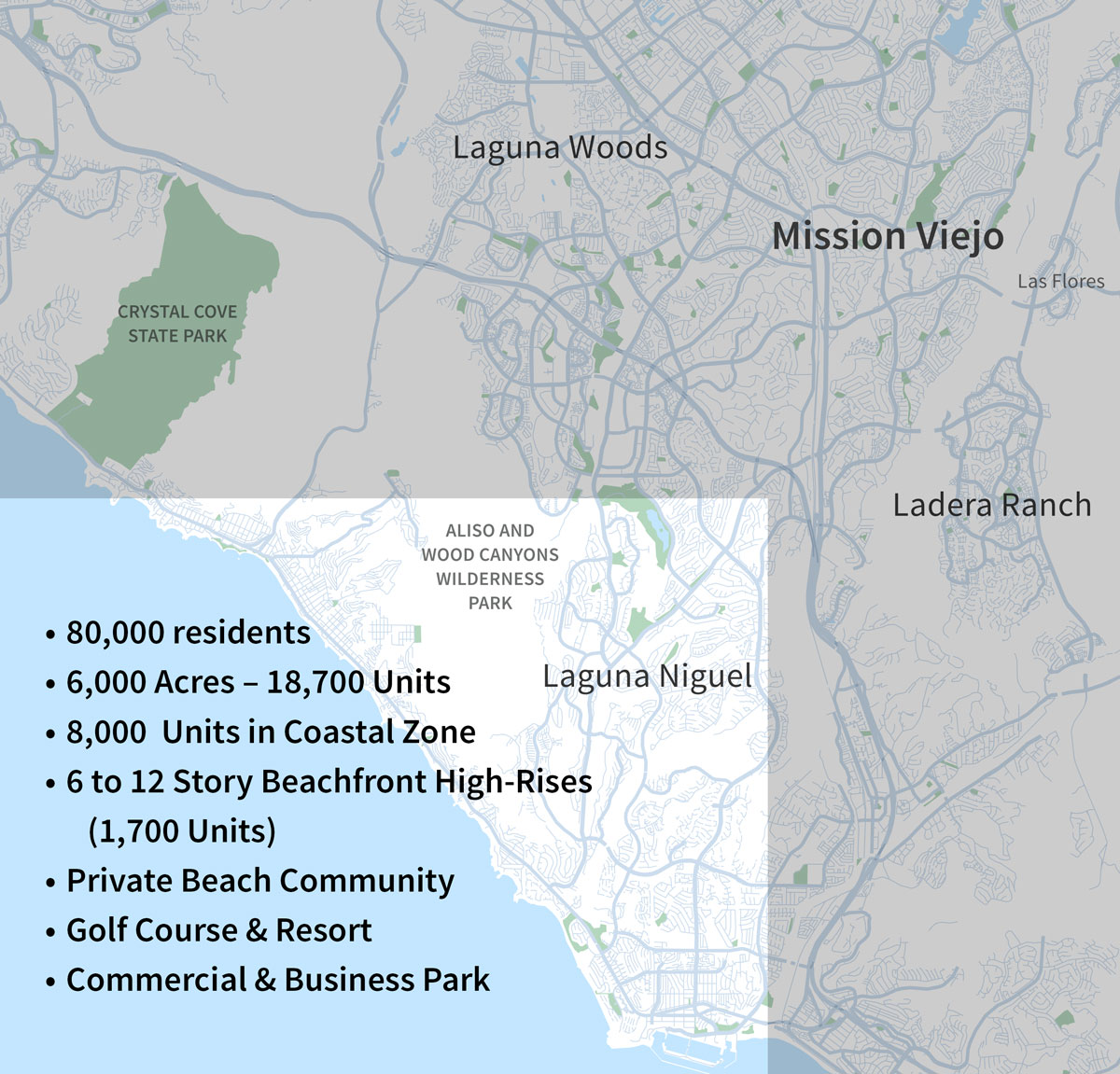

In 1976, the Coastal Commission became a permanent agency by a narrow vote of the California Legislature. The press credited this slim victory to the skillful politics and maneuvering of Governor Jerry Brown. In reality, that victory belonged just as much to Mel Lane and Joe Bodovitz as it did the first-term Democratic governor. For four years, they guided the fledgling agency to permanence, developing the guidelines and process that would come to govern California’s coastline. They battled with development projects such as Avco and Irvine in Orange County, and Sea Ranch in Sonoma, establishing the regulatory principles that later coastal developments would follow: build smaller, secure public access, and protect scenic views and the environment. Their work instilled public confidence in a controversial and unprecedented program. At the same time, their partnership bridged the structural divide between expert staff and appointed commissioners, forming a cohesion between the two bodies of the young agency. Those formative years, to be sure, would prove a golden age for the California Coastal Commission.

Avco Community Developers’s Laguna Niguel Proposal

The Development ultimately included only 3,000 units, no high-rise buildings, a public golf course, a 7.5 acre public park on the coast, and a 25 acre public park further inland. MapBox with Open Street Map Data

1978-1985

Mounting Waves of Tension

Executive Director: Michael Fischer

The resignation of Mel Lane and Joe Bodovitz in 1978 initiated the first period of transition within the commission. Both men were viewed as father figures among commissioners and staff alike, a level of respect that played no small role in the cohesion they were able to create within the agency. By all accounts, Bodovitz’s successor was well suited to continue advancing the commission smoothly along this same path. Michael Fischer was no stranger to the agency. An alumnus of U.C. Berkeley’s Urban Planning program and a former researcher at SPUR, Fischer had served as the executive director of the commission’s North Central Coast Region from 1973 to 1976. After a stint in Governor Jerry Brown’s Office of Urban Planning, he returned to the commission to replace Joe Bodovitz. Such experience instilled confidence. Few things, however, could have prepared Fischer for the mounting waves of tension he was about to confront.

This tension, ironically, first arose significantly within the fold of the Democratic Party. Throughout the long sixties era, Democrats had offered steady support for environmental causes, of which the Coastal Commission was no exception. And with the Party holding the governorship, both houses of the legislature, and thus all twelve appointments to the commission, there seemed no reason to expect a turn of tide.

Michael Fischer, Executive Director from 1978 to 1985.

Read Michael Fischer's 1993 Oral History conducted by the Oral History Center, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley

EarthAlert!

By all accounts, Bodovitz’s successor was well suited to continue advancing the commission smoothly along this same path. Few things, however, could have prepared Fischer for the mounting waves of tension he was about to confront.

But by 1978 support for the commission began to wane within the Party. This withering largely stemmed from coastal developments like Sea Ranch and Malibu, where the agency’s regulations—and in some cases construction moratoriums—directly affected the homes of Democratic policymakers and their wealthy liberal donors. Endorsing environmental regulation was one thing; having one’s own beach house subject to that regulation was quite another. As Michael Fischer recalled, the political pressure was intense. “People were fighting mad…state legislators found it impossible to go to a cocktail party anywhere in the state and not find somebody who was pissed off at the Coastal Commission.”

Other factions of the Democratic Party were also adversely affected by the commission’s policies, most notably organized labor. In many respects, coastal development was one of the few areas where the interests of union labor and industry coalesced. The agency’s push to build smaller—as seen in the developments of Sea Ranch, Irvine, and Avco—not only slashed the profits of developers and property owners, but consequently also the job prospects and wages of trade unionists. Thus for organized labor, the commission’s opposition to proposed developments, such as those in the Bolsa Chica wetlands, Monterey’s Elkhorn Slough, and offshore oil derricks on the North Coast, only added further insult to fiscal injury.

It was within this political context that Michael Fischer began to experience friction with the Democratic Party and its appointees. In Sacramento, Democrats in both the Assembly and Senate legislated their own solution to the Sea Ranch controversy. Known as the Bane Bill, the legislation essentially affirmed the commission’s requirements of coastal access and maintaining scenic views, while exempting new single-family homes in the development from further permit conditions. The bill also awarded the Sea Ranch Association $500,000 in compensation.

That same year, Democrats passed legislation removing the affordable housing statute from the Coastal Act—a policy which had resulted in the construction of approximately 1,300 moderate-income units within California’s coastal zone between 1976 and 1981. To Fischer, such actions reaffirmed his view of the distaste most politicians held for plans. “Elected officials tend to hate planning,” he would later state, “because it restricts their flexibility and it locks them in to a plan. So when a donor or a voter or a landowner wants them to do something, they usually have to try to amend the plan.”

Sea Ranch in Sonoma County Democrats in both the Assembly and Senate legislated their own solution to the Sea Ranch controversy. Known as the Bane Bill, the legislation essentially affirmed the commission’s requirements of coastal access and maintaining scenic views, while exempting new single-family homes in the development from further permit conditions. The bill also awarded the Sea Ranch Association $500,000 in compensation. Of Houses via Flickr

“People were fighting mad…state legislators found it impossible to go to a cocktail party anywhere in the state and not find somebody who was pissed off at the Coastal Commission.” —Michael Fischer

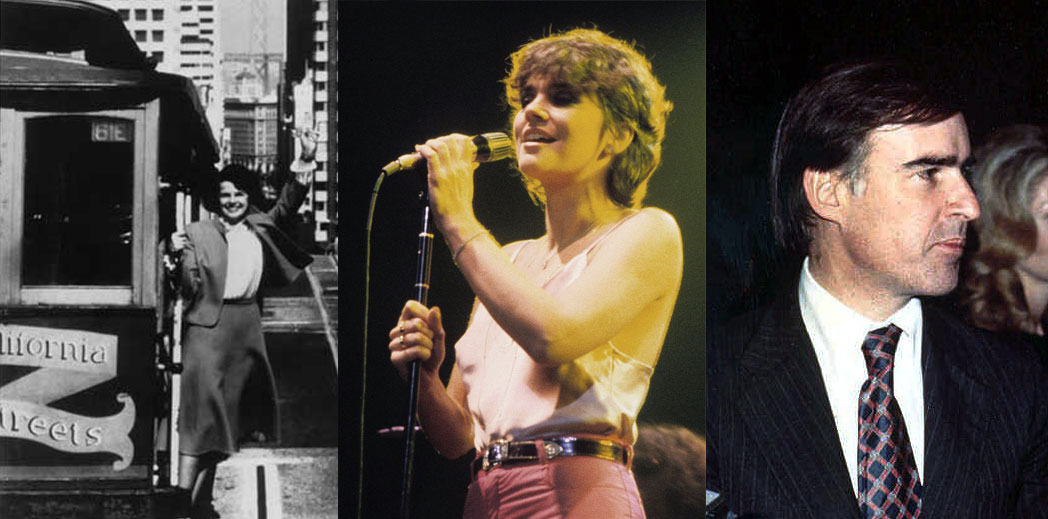

This lack of flexibility ultimately led to Fischer colliding head-on with some of the state’s Democratic lawmakers. When San Francisco Mayor, and future U.S. Senator, Dianne Feinstein installed a fence at her Monterey beach house in an effort to cordon off her beachfront backyard, Fischer’s staff cited her for violating the Coastal Act. “Diane was just devilish to deal with,” Fischer recalled. “She was brutal to staff and impatient with the law.” Similar legal action was taken against musician Linda Ronstadt, when she and her Malibu neighbors had a seawall built without a permit. That the music star happened to be the girlfriend of Governor Jerry Brown held no sway with Fischer, fueling further tension between the staff, the governor’s office, and Brown’s appointees on the commission. In 1978, such tension exploded following the Agoura-Malibu fire, which burned down a large swath of the affluent Southern California coastal community. Responding to fears that the commission would use the required rebuilding permits to exact long-coveted easements for coastal access from Malibu homeowners, Brown pushed for emergency exemptions and even derided commission staff as “bureaucratic thugs.” In response, the staff publicly sported t-shirts emblazoned with the slogan “Coastal Bureaucratic Thug and Proud Of it.”

"Coastal Bureaucratic Thugs" Stanford University legal scholar and former Coastal Commissioner Meg Caldwell modeled a t-shirt the agency’s staff distributed in an ironic response to Gov. Brown’s memorable denunciation. Bill Lane Center for the American West

"Coastal Bureaucratic Thugs" Stanford University legal scholar and former Coastal Commissioner Meg Caldwell modeled a t-shirt the agency’s staff distributed in an ironic response to Gov. Brown’s memorable denunciation. Bill Lane Center for the American West

This mounting tension reached a crescendo under Governor George Deukmejian. The conservative Republican waged a full-scale assault on the young regulatory agency. His 1982 platform not only included the laissez-faire ideals of lower taxes and smaller government, but also the pledge to abolish the California Coastal Commission. The threat spurred Michael Fischer to jump into partisan politics. “I behaved in a somewhat uncharacteristic way for a state bureaucrat,” he would later admit regarding his involvement on behalf of Democratic candidate Tom Bradley. “I became active, and visibly active, in the Bradley campaign.” Indeed, it was an unprecedented step for the executive director of a state agency. Throughout the fall, Fischer could be heard on radio ads and stump speeches telling Californians, “This year vote as if though the future of the coast is at stake, because it is!”"

“I behaved in a somewhat uncharacteristic way for a state bureaucrat,” he would later admit regarding his involvement on behalf of Democratic candidate Tom Bradley. “I became active, and visibly active, in the Bradley campaign.” Indeed, it was an unprecedented step for the executive director of a state agency. Throughout the fall, Fischer could be heard on radio ads and stump speeches telling Californians, “This year vote as if though the future of the coast is at stake, because it is!”"

Fischer’s principled lack of flexibility led to clashes with prominent members of the Democratic political establishment. When San Francisco Mayor, and future U.S. Senator, Dianne Feinstein (left) installed a fence at her Monterey beach house in an effort to cordon off her beachfront backyard, Fischer’s staff cited her for violating the Coastal Act. Similar legal action was taken against musician Linda Ronstadt (center), when she and her Malibu neighbors had a seawall built without a permit. That the music star happened to be the girlfriend of Governor Jerry Brown mattered little to Fischer, fueling further tension between the staff, the governor’s office, and Brown’s appointees on the commission. Wikimedia Foundation

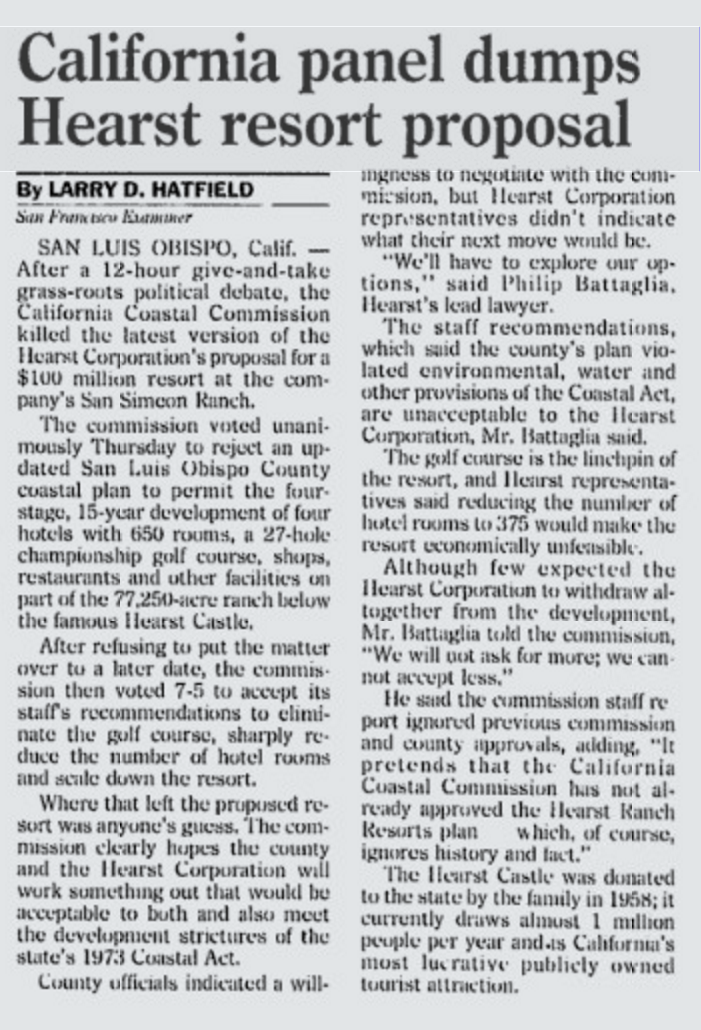

George Deukmejian may not have had the votes to abolish the Coastal Commission as he entered the Governor’s Office in 1983, but he did hold executive powers that could be used against the agency—powers he exercised almost immediately. He used the line-item veto to slash over $2 million from the commission’s budget. The fiscal toll resulted in the closure of the agency’s Eureka office, with others slated to follow. Such cuts also saw commission staff decline by half, from 220 to 110. Moreover, Deukmejian’s four appointments to the Coastal Commission mounted a steady campaign to oust Michael Fischer. For nearly two years, Fischer faced the looming threat of dismissal, with six votes—four Republican, two Democrat—favoring to appoint a new executive director. Although the opposing forces on the commission could not secure the needed seventh vote to fire Fischer, the bipartisan push underscored the heightening tension that now divided the agency’s two bodies.

Michael Fischer finally resigned in the summer of 1985. Indeed, conflict ensnared his tenure as executive director from the start. Responding to public demands, especially those of donors, both political parties sought to alter the agency’s direction. Democrats withdrew support, legislated their own solutions, and advocated for an easement of coastal enforcement. Republicans under Governor Deukmejian went on the attack, seeking not as much to change the commission as to dismantle it. Amid the rise of political pressure, many appointed commissioners responded accordingly; Fischer and the staff increasingly bore the brunt.

Yet in many respects, the tension that consumed the Coastal Commission by the time of Fischer’s resignation proved as much structural as it was political. Commissioners, as appointed civil servants, had to address the demands of the public. They also had to answer to the elected officials who installed them. Both forms of “accountability” at times conflicted with the agency’s independent staff. Experts in their field and devoted to the conservationist cause the commission embodied, their recommendations were based on science, law, environmental study, and long-term planning. To wit, the winds of politics and public opinion held no sway. As Michael Fischer aptly observed, the inherent conflict that afflicted environmental regulation as a whole was clearly seen in the very structure of the commission itself: “The needs of tomorrow never, ever have quite the standing as the urgent demands of today.” Mounting waves of tension ultimately forced Fischer to resign. Under his successor, those waves would heighten to a near storm surge.

George Deukmejian, California’s two-term governor from 1983 to 1991. Governor Deukmejian may not have had the votes to abolish the Coastal Commission, but he used the line-item veto to slash over $2 million from its budget, cuts that saw commission staff decline by half, from 220 to 110. Official Portrait via Wikimedia Foundation

1985-2011

In the Eye of the Storm

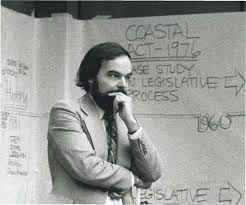

Executive Director: Peter Douglas

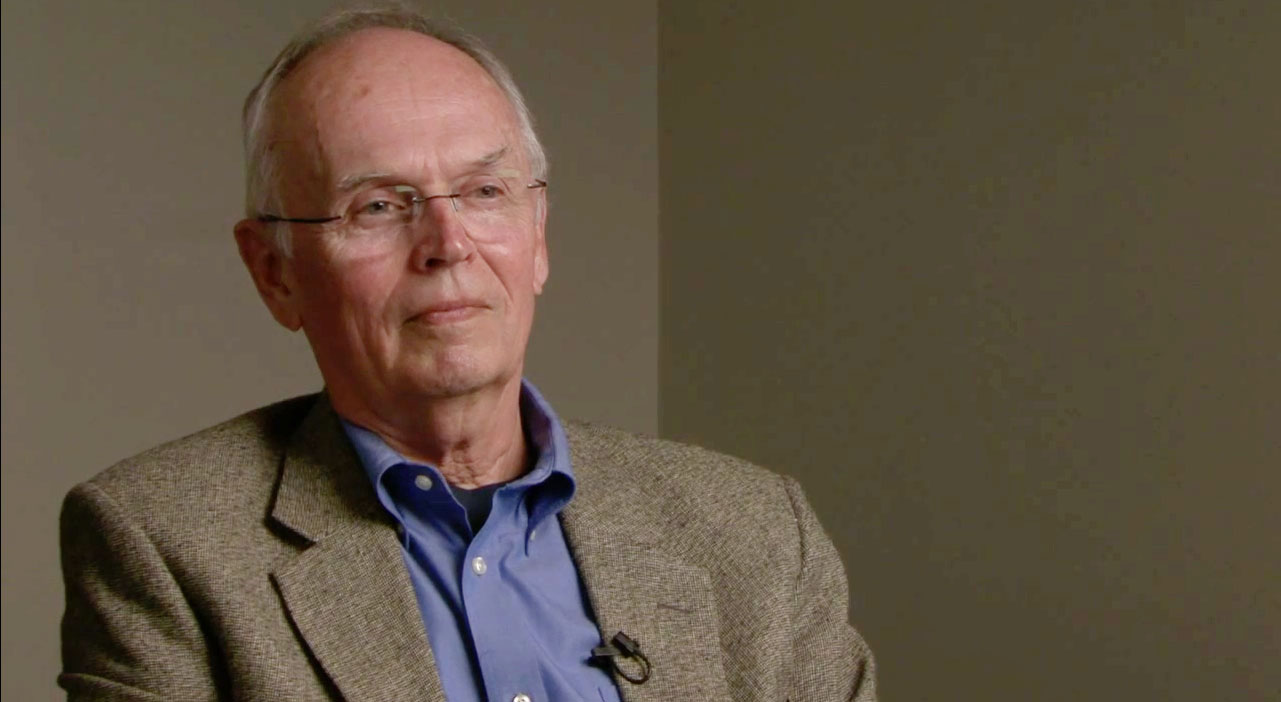

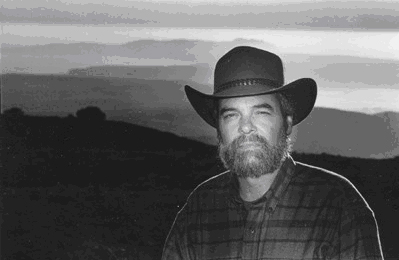

Peter Douglas entered the executive directorship of the Coastal Commission with the same passion and purpose he exhibited throughout the agency’s creation. His appointment upon Fischer’s resignation was logical, for no one rivaled Douglas’ experience and expertise. But it was also controversial. Initially stating that he was not going to pursue the position, Douglas was ultimately appointed on an 8 to 4 vote. An alumnus of UCLA Law School and a seasoned legislative aide in the state Assembly, he wrote both the 1972 Coastal Initiative and the 1976 Coastal Act. He even served as the agency’s deputy director from 1976 to his promotion in 1985, a position he essentially created for himself. For many, Peter Douglas’ ascension to executive director was seen as natural as the shoreline the agency governed: he was heading the very commission he helped create.

Over the next twenty-six years, Douglas would assume a stature few civil servants in California could match. He waged epic battles against Republicans and Democrats, pushed the boundary of the agency’s jurisdictional reach, and stood unyielding in the face of well-funded legal challenges. And in the process, he forged a public presence that went well beyond those of his predecessors, even including Michael Fischer’s 1982 foray into electoral politics. For most Californians, Peter Douglas became synonymous with the California Coastal Commission. His actions over the decades certainly garnered an equal share of supporters and critics. But they also further strained the mounting tension between commissioners and agency staff to a near breaking point. Waves of tension may have greeted Douglas upon assuming the directorship, but during his tenure, such conflict culminated into a storm.

Peter Douglas, executive director of the Coastal Commission for 26 years, from 1985 to 2011.

California Coastal Commission

An alumnus of UCLA Law School and a seasoned legislative aide in the state Assembly, Douglas wrote both the 1972 Coastal Initiative and the 1976 Coastal Act.

Douglas met that storm head on from the beginning. He adamantly refused Governor Deukmejian’s orders to close the commission’s offices in Santa Cruz and Santa Barbara, and successfully spearheaded the opposition to a proposed Walt Disney theme park on Long Beach Harbor. The $3 billion project, according to staff, would have not only blocked scenic views and caused untold environmental damage, but also fill in over 250 acres of ocean. Douglas similarly guided the commission’s denial of the Hearst Corporation’s plans to develop its coastal property in San Simeon, efforts that ultimately left the scenic shoreline, including the famed San Simeon point, untouched. A preservationist at heart, he worked extensively with various government agencies to place large swaths of California’s coast under the protection of state parks, as seen with Tomales Bay in Marin, Garrapata State Park in Big Sur, and Crystal Cove in Orange County. As Douglas would often tout, “our major accomplishments are what you don’t see: the subdivisions not built, the wetlands not filled in, the views not spoiled.”

To the chagrin of businessmen and developers, his protectionist thrust and honed political skills held sway more often than not. The commission followed his recommendation to deny Pebble Beach Company’s proposal to cut down thousands of rare Monterey Pines for the construction of a new golf course. He initiated a successful legal battle with the powerful Southern Pacific Company to turn its old rail line on the Monterey Peninsula into a public bike path and park instead of high-rise condominiums. And when oil companies, backed by President Ronald Reagan, sought to initiate offshore drilling along California’s coast, Douglas stood steadfast in maintaining the hard-fought moratorium of his predecessor.

Under Douglas’ leadership, staff reports increased in volume and legal expertise. On occasions when the commissioners chose to ignore his recommendations, Douglas would use the press to take his argument to the public. In one famous decision, the commission overrode the staff recommendation to deny a substantial residential development on the Bolsa Chica wetlands in Huntington Beach. With Douglas’ support, citizen groups in Orange County filed suit, using the original findings in the staff report as the basis. The superior court reversed the commission’s action, validating the analysis of Douglas and the staff. The developers appealed, but to their chagrin the appellate court went even further, extending full Coastal Act protections to sensitive habitat even when it is degraded and less than pristine. That published decision is still cited today.

To be sure, his actions earned him the admiration of many throughout the state. They also fueled an ever-growing throng of critics. Supporters hailed Douglas as a coastal patriot, the protector of the sea. Opponents, however, held strongly different views. Epithets such as socialist, zealot, cultist, and dictator were commonly cast at Douglas, as development interests and property owners alike grew frustrated by his strong enforcement. “I know I’m not going to convince you Mr. Douglas,” one Malibu resident fumed. “You’re a demagogue and a fanatic…preaching the virtues of self-abnegation as a civic duty.” Lawyers with the Pacific Legal Foundation, frequent foes of Douglas and the commission, echoed such sentiments. “Douglas has the attitude of a ruler rather than a civil servant,” one attorney argued. For most critics, Douglas’ decades-long tenure went well beyond its usefulness. As one San Diego homeowner lamented, “Any other panel formed to conduct the public’s business would have long ago replaced an executive director who arrogated to himself the powers over decision makers and citizens that Douglas does.”

In like fashion, Douglas’ actions also repeatedly stoked the tensions between staff and commissioners. In 1991, those tensions flared with a public hearing on his possible dismissal. Commissioners David Malcolm and Mark Nathanson led the effort against Douglas *, circulating what was later called a “horrendous, outrageous charge” to prompt his ouster. Both Malcolm and Nathanson were appointed by Democratic Assembly Speaker Willie Brown, and had tried for years to get Douglas, in his words, “to play ball.” The rumor, initially spread by a San Francisco law firm long at odds with Douglas, had little effect. The commissioners voted 10-0 in Douglas’ favor, with Malcolm and Nathanson abstaining. The hearing, however, offered a frustrated commission the opportunity to reel in its executive director. Some commissioners complained about Douglas’ bad relations with Governor Deukmejian, while others took aim at his public posture. “He makes policy pronouncements as if he speaks for the 12 members of this commission,” one appointee averred. Most agreed changes were in order. The commissioners pushed for Douglas to hire more women and minorities, and to accelerate the permit process. They also implemented an annual performance review for the executive director. As Chairman Thomas Gwyn stated, the hearing’s purpose was to make needed changes and, above all, “to get Peter on track.”

Five years later, tensions again reached a breaking point between the agency’s two bodies, as commissioners once more weighed the prospect of dismissing Douglas. This time, however, Republicans led the effort. With the GOP holding both the governorship and a majority in the state assembly, the Party for the first time commanded eight appointments on the commission. And almost immediately, Republican leaders called for Douglas’ ouster. Governor Pete Wilson had grown tired of the director’s recalcitrance. So too had Resource Secretary Doug Wheeler, who made no secret that he wanted Douglas fired, especially after the ordeal of the Bolsa Chica development. Yet as the hearing commenced in Huntington Beach that July, their attempt fell flat. Hundreds of supporters flooded the event, many donning signs lambasting the commissioners as “Pirates” for wanting to “loot the coast and make Peter Douglas walk the plank.” The outpouring of public support spurred cold feet among some GOP appointees, particularly two commissioners running for local office in coastal districts. Fearing a voter backlash, they reversed their stance at the last minute, denying Douglas’ opposition the needed seven votes. The executive director reveled in victory. “I think it is an affirmation of public support for a high-quality, professional staff that is nonpartisan,” he declared after the hearing. “Our [the staff’s] job is not to make friends, but to carry out legal determinations in a fair and objective manner.”

Douglas emerged from the hearing with job intact, but some commissioners were still determined to bring Douglas and his staff to heel. The commission instituted an annual audit of the staff, and again pushed for a “more streamlined, user-friendly” permit process. Above all, commissioners wanted the hearings to reset the balance of power between the two bodies. “We want to make sure that policymakers run the staff,” Commissioner Tim Staffel, a Pete Wilson appointee, asserted, “not the staff run the policymakers.”

Douglas successfully spearheaded the opposition to a proposed Walt Disney theme park on Long Beach Harbor. The $3 billion project, according to staff, would have not only blocked scenic views and caused untold environmental damage, but also fill in over 250 acres of ocean.

Pasadena Star News, January 18, 1998

Tomales Bay Wikimedia Foundation

Douglas’s actions earned him the admiration of many throughout the state. They also fueled an ever-growing throng of critics. Epithets such as socialist, zealot, cultist, and dictator were commonly cast at Douglas, as development interests and property owners alike grew frustrated by his strong enforcement.

* David Malcolm and Mark Nathanson would both later be convicted on corruption charges. Malcolm for his illegal activity while serving on the San Diego Port Commission, and Nathanson for accepting bribes during his tenure on the Coastal Commission.

Throughout his twenty-six-year tenure as executive director, Peter Douglas survived over a dozen attempts at dismissal. And like his predecessor, the tension he confronted proved just as much structural in root as it was political. Indeed, Democrats and Republicans alike sought to replace Douglas, responding, as they had before, to the rising demands of donors, various interest groups, and the public. Appointed commissioners followed suit. As Douglas would remark after the failed attempt in 1996, “It’s fine if they want me out for political reasons, but I want the world to know that.” Nevertheless, politics was just one front of the storm he both weathered and fueled as executive director. By any measure, Peter Douglas was a strong executive, a formidable figure who enforced the Coastal Act with the same unwavering resilience and public presence he exhibited when helping to create it. He battled developers, negotiated ruthlessly with elected officials and property owners, and even periodically confronted his own commissioners. Throughout, he achieved what few state bureaucrats could—he created a brand that largely made him synonymous in the public’s eye with the very state agency he directed. When situated, however, within an agency structure already prone to internecine conflict between expert staff and appointed commissioners, Douglas’ actions at times pushed this inherent tension to a breaking point.

Peter Douglas retired in the fall of 2011 for health reasons, ending one of the longest, and more contentious, senior civil servant careers in California history. For Douglas, the storm-like tension he navigated during his twenty-six year tenure between business, property owners, commissioners, environmentalists, and staff was par for the course. “The Coastal Commission and Coastal Act were born in the crucible of conflict,” he observed toward the end of his career. “It’s a controversial program…[and] my job is a very controversial position.” Upon his retirement, many in the press ruminated openly on Douglas’ ability to last so long in that controversial position, or as NPR’s John McChesney put it, his ability to “defy gravity.” The question not pondered, however, was how someone could actually survive as executive director in his wake. Every action, according to Isaac Newton, produces an equal and opposite reaction—a law that works as robustly for the political arena as it does the natural world.

Peter Douglas in 1976 California Coastal Commission

2011-2016

Of Wakes & Riptides

Executive Director: Charles Lester

It was amid these tides of tension that Charles Lester entered the executive directorship of the California Coastal Commission in 2011. And it was these same tides that would ultimately bring about his dismissal nearly five years later.

In many respects, Lester embodied the expertise of the agency’s new generation. He held a Ph.D. and law degree from U.C. Berkeley, and worked in academia before joining the commission in 1997. Rising through the ranks, he served as the agency’s senior deputy director before assuming the top staff position. Impressed by his intellect and work ethic, Douglas had been mentoring Lester as a potential successor for years.

But no amount of experience and expertise, could have arguably prepared anyone to lead the agency in the wake of Peter Douglas. Over the decades, frustration over the inability to control the commission had intensified in Sacramento, and animosity had grew among property owners and the development community. Douglas had seemingly navigated the eye of this storm with ease. To expect those who followed to do the same would prove as naive as it would unfair.

Charles Lester felt the strain and pressure of this storm almost immediately. In rapid succession, projects long opposed by the staff under Douglas resurfaced on the commission’s agenda. SNG, for instance, had worked since 1998 to garner commission approval for its eco-resort on 40 acres of sand dunes just north of Monterey. Similarly, David Evans—famed guitarist of the rock band U2—fought for over a decade to obtain approval for five mansions on the coastal bluffs above Malibu. When first proposed, Peter Douglas dismissed the development as one of the most environmentally damaging projects he had ever seen. Both were approved under Lester, as the result of litigation settlements supported by the post-Douglas commission. Other controversial proposals followed, such as sand replenishment in Malibu, a major residential development at Banning Ranch in Newport, and a desalination plant in Huntington Beach. While not atypical, these and other high-profile projects placed Lester in a crucible of controversy before he’d had an opportunity to get his “sea legs.”

Lester faced similar pressure from the appointed commission itself. Under Peter Douglas, the independence of the staff was strongly defended. Charles Lester ultimately experienced the riptide of this defense as some commissioners sought to reassert their position during his tenure. They demanded more responsiveness from staff, a faster flow of information and access to experts, and, ultimately, further involvement in the analysis and recommendation process. Lester complied to the best of his ability. He instituted a monthly executive director report, and a detailed “dashboard” to track the commission’s progress on its strategic plan goals. He significantly reduced processing times for appeals, reduced the backlog of Local Coastal Plan amendments, gained legislative approval for administrative penalty authority, and secured the largest budget augmentation in the agency’s history. Yet Lester resisted commissioners’ attempts to get directly involved in the analysis process, and was reluctant to cede the agency’s jurisdiction over new fees at State Park beaches. On February 10, 2016, the commission voted to dismiss Peter Douglas’ hand-picked successor.

Lester in an interview for the documentary “Heroes of the Coast” Courtesy EarthAlert!

Over Peter Douglas’ twenty-six years, animosity had intensified largely among elected officials, property owners, developers, and appointed commissioners over the actions of the California Coastal Commission. Douglas had seemingly navigated the eye of this storm with ease. To expect those who followed to do the same would prove as naive as it would unfair.

In the wake of the hearings at Morro Bay, many saw the firing of Charles Lester as the work of development interests; “capture,” some asserted, had finally come to the California Coastal Commission. Yet tension, rather than capture, stands as a more accurate explanation, as Lester’s firing had less to do with outside development interests than the commissioners’ views about the role of staff and the executive director. After the hearing Lester himself would observe, “This was about a power struggle between the commission and staff,” noting that “some of this might be wanting to finish the transition away to something different from the legacy of Peter Douglas.” That legacy went well beyond Charles Lester. By any measure, his actions as executive director stood as a better fit for the professional and pragmatic mold of Joe Bodovitz than the controversial Peter Douglas.* He waged no public campaign against development interests, office holders, or commissioners. In fact, his public presence was minimal by comparison to his two predecessors, preferring instead to work behind the scenes. Nor is there a single charge on record of Lester overstepping his jurisdictional bounds. At root was the structural tension within the Coastal Commission between commissioners and staff.

In many respects, Lester’s dismissal was historic. He was the first executive director of the agency removed by commissioners. More importantly, the tides of tension which underpinned that action existed long before he took office. They mounted during the tenure of Michael Fischer, intensified under Peter Douglas, and ultimately crashed into Charles Lester. Indeed, remnants of these tides could be seen throughout the proceedings, from the use of staff audits and performance reviews to the oft-cited reforms of staff diversity * and a more streamlined permit process. In short, the proceedings at Morro Bay had a much longer history than many recognized.

* Of the comparisons often made between Douglas and Lester, their contrasts have received more attention than their similarities. Chiefly overlooked among the latter are dedication and courage. The executive directorship of the Coastal Commission is a thankless job, a position, in the words of former commissioner Mel Nutter, “permanently situated between the dog and fire hydrant.” The dedication of those who assume the position is without question. So too is the courage of Douglas and Lester to do so when they did. Not many would have stepped forward to guide the agency staff through the difficult days of Governor George Deukmejian. And in like fashion, few would have accepted the nod to fill the large shoes — or more accurately, Birkenstocks — of Peter Douglas.

* Racial diversity within environmental movements and programs has a complicated history rooted in place. Many communities of color became active in regard to environmental concerns when such issues affected their health and families. Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers addressed pesticides in agriculture; communities in industrialized areas challenged air pollution and water quality. That some have charged a lack of diversity at the Coastal Commission has much more to do with the demographics of the state’s coastline — especially after the Legislature struck down the moderate housing requirement in 1981 — than any operation at the agency.

The Bixby Creek Bridge in Big Sur Wikimedia Foundation

Over the last four decades, the California Coastal Commission has forged an impressive list of achievements, a list even more noteworthy in light of the tension that has periodically flared between the agency’s two bodies: the expert staff and the appointed commissioners. While the commission may not be the only state agency afflicted by such conflict, what may set the Coastal Commission apart, is the very area it regulates, namely the most desirable coastline in the Western Hemisphere. Conflict within this area is unavoidable. So too, is the structural tension within the agency that regulates it.

Still, the fluctuating tides of tension between staff and commissioners should not be seen as the agency’s defining factor. The history of the Coastal Commission is filled with examples of both bodies bridging differences and working together to protect the state’s coastal resources. As Mel Lane often touted, “reasonable, fair-minded people dealing with facts in an unemotional way will largely find themselves in agreement.” That this ideal has proven a difficult—if not elusive— bar to meet, both past and present, goes without saying. But today, we can look at many examples along California’s coast that give testament to the collaborative work of the commission, from pristine public shores to carefully planned residential communities.

These many achievements aside, recognizing the inherent tension within the commission is essential. It provides a more accurate context for Charles Lester’s dismissal in February 2016, and a better understanding of the agency’s operation over the last forty years. Moreover, grappling with the roots and realities of this fundamental conflict will prove vital as the Coastal Commission moves forward. Under the interim directorship of Jack Answorth, an agency veteran of over 27 years, the commission plans to embark on a lengthy, and surely contentious, search for a new executive director. Indeed, when complete the selection will mark a new chapter in the history of the California Coastal Commission. How that new chapter develops will largely depend on how well both commissioners and staff navigate the tides of tension.

Correction

A photo caption originally misidentified the congressional candidate Julian Camacho as Cesar Chavez at a 1972 rally.

For more information

Explore the California Coastal Commission Project at the Bill Lane Center for the American West.

The Coastal Commission is not the only state agency afflicted by such conflict. What may set the Coastal Commission apart, however, is the very area it regulates, namely the most desirable coastline in the Western Hemisphere.

Todd Holmes is a Historian and Associate Academic Specialist with the Bancroft Library’s Oral History Center at UC Berkeley. He is also an Affiliated Scholar with the Bill Lane Center for the American West at Stanford University. This essay is based on over two years of research conducted on behalf of the Bill Lane Center’s California Coastal Commission Project. This research included extensive work in the Coastal Commission records at the California State Archives, interviews with former staff and commissioners, as well as the valuable oral histories of the Bancroft Library.

The author would like to thank Bruce Cain and Stanford’s Bill Lane Center for the American West for three years of intellectual growth, support, and friendship. He would also like to thank Joan Lane and the Lane family for their generous financial support of both the Center and its California Coastal Commission Project. A special thanks goes to Martin Meeker and the Bancroft Library's Oral History Center at U.C. Berkeley, as well as many colleagues for their assistance: Brianna Brown, Lauren Brown, Andrew Elott, Mauricio Antunano, Magellan Pfuke, Dan Reineman, Marika Sitz, and Rachel Winslow.

Lastly, a very special thanks to Geoff McGhee for his production and editorial acumen.